It is well known that the night of the 15th of June closed on the Duke of Wellington receiving word while he attended The Duchess of Richmond’s ball in Brussels that Napoleon had attacked on the opposite side of Brussels to the point where Wellington was convinced Napoleon would approach. Wellington had his army ready to defend the road at Mons.

It is well known that the night of the 15th of June closed on the Duke of Wellington receiving word while he attended The Duchess of Richmond’s ball in Brussels that Napoleon had attacked on the opposite side of Brussels to the point where Wellington was convinced Napoleon would approach. Wellington had his army ready to defend the road at Mons.

Napoleon attacked on the opposite side in two places, in the area beyond the village of Lingy, where Blucher’s Prussian army were gathered, and at Quatre-Bras, where a farm still stands on the edge of the crossroads.

There was one thing each of the leaders knew – the other would approach on a road, and wanted ownership of the roads. The roads between Brussels and Lingy were straight old Roman roads, perfect for an army to advance on, pulling their cannons and ammunition carts with them. But Wellington had been so convinced that Napoleon would attack on the North of Brussels he did not even have anyone in place to defend the significant crossroads of Quatre-Bras which was 22 miles from Brussels and about half way between Lingy and Mont St Jean where the Battle of Waterloo took place two days later.

Wellington admitted that he had been ‘humbugged‘ when he heard the news in the coach house of the Duke of Richmond’s residence which had been converted into a ballroom for the night, he immediately withdrew to a room to study the maps and then messages were sent out to rally the British army and send them out onto the road to march towards the battles, miles away.

There was some luck on the Allied forces side, the Prince of Orange’s Dutch forces were closest to Quatre-Bras, and some of his men saw the French cavalry scouting around the undefended crossroads. When the Prince of Orange heard he immediately sent a battalion back to defend it and a message was sent to Wellington to tell him they expected to be attacked there at Dawn, and that each man only had ten rounds of ammunition left.

The first soldiers marched out of Brussels and the surrounding area by moonlight, at two in the morning, while others were gathered but had time to sleep on the streets where they’d been mustered.

Johnny Kincaid of the 95th Rifles records. ‘But we were every instant disturbed by ladies as well as gentlemen; some stumbling over us in the dark, some shaking us out of sleep, to be told the news...’

Another eye witness, a female who had travelled from England with her family as a spectator recorded how the streets of Brussels filled with soldiers and confusion. ‘Officers looking in vain for their servants, servants running in pursuit of their masters, baggage wagons were loading, trains of artillery harnessing… As the dawn broke the soldiers were seen assembling from all parts of town, in marching order, with their knapsacks on their backs, loaded with three days’s provisions… Numbers were taking leave of their wives and their children , perhaps for the last time… One poor fellow immediately under our windows, turned back again and again to bid his wife farewell, and take his baby once more in his arms; and I saw him hastily brush away a tear with the sleeve of his coat as he gave her back the child for the last time, wrung her hand, and ran off to join his company.‘

Lieutenant Basil Jackson described the exodus as the men marched out of the city. ‘First came the battalion of the 95th Rifles, dressed in dark green, and with black accoutrements. The 28th Regiment followed, then the 42nd Highlanders, marching so steadily that the sable plumes of their bonnets scarcely quivered.‘

Wellington reached Quatre Bras around 9.30 am, some of the British army had already arrived, and he saw that they were positioned as effectively as they could be. He rode on then to meet Blucher, the head of the Prussian army, at the Brye windmill near Lingy, Wellington warned Blucher that his position

would be impossible to defend, as Blucher had placed his army in a hollow, giving the French the advantage of a hill to place their cannon on, and they were also positioned along a stream which had a narrow point facing the French, which left the soldiers at the front exposed to attack from more than one side. The two men agreed then that they would come to the others aid, depending on how the day progressed and where Napoleon focused his attack.

He attacked in both places, he sent Marshal Ney, who had arrived hours before, to lead the force attacking Quatre-Bras, and he lead the forces attacking the Prussians at Lingy, taking up a position in a windmill to be able to oversee the battle.

Had Ney attacked early there would have still been only 8,000 in the Allied forces compared to Ney’s 40,000 men, but Ney did not attack until the afternoon, and every hour that passed more soldiers reached the crossroads of Quatre-Bras.

Ney’s men were initially in this farm further along the road, and at the rear of this was a lake, meaning the majority of fighting took place in the mile between this farm and the crossroads. Below are pictures of the field where a lot of the fighting occurred, and the old Roman Road which was surrounded by a wood that meant artillery could hide and just shoot anyone attempting to approach.

The Roman road surrounded by a wood in 1815 where artillery hid and slaughtered anyone attempting to progress along the road.

One the first companies to arrive were the 42nd Regiment, the Highlanders, who the night before had been dancing jigs at the Duchess’s ball. They were sent in immediately. They were hidden amid the tall rye crop, which I talked about in a previous post on Waterloo, ‘we strode and groped our way through as fast as we could. By the time we reached the field of clover on the other side we were very much straggled; however, we united in line as fast as time and our speedy advance would permit. The Belgic skirmishers (the men who were positioned ahead of the artillery, in twos, who acted like snipers, trying to bring down officers) retired through our ranks and in an instant we were on their victorious pursuers. Our sudden appearance seemed to paralyse their advance. The singular appearance of our dress, (kilts and tartan bonnets) combined no doubt with our sudden debut, tended to stagger their resolution: we were on them.’

But what the highlanders had not realised was that the cavalry approaching on their flank, who they thought were the Brunswickers, part of the Allied army, were in fact the French cavalry. When it was realised they hurried into the closest format they could achieve to a square, even trapping some of the French cavalry among them. Who were pulled from their horses (this was the moment I mentioned when I spoke about squares, when the Prince of Orange told the 69th not to form, and they were lost).

The Highlanders were scandalized as they formed a square, when their Batallion commander who had already been injured and was being carried off the field by four men, was attacked. He and the four men carrying him were killed. The Highlanders considered it murder, not war. They attacked the French prisoners after the battle in revenge.

The Battle at Quatre-Bras went on for hours, with Ney continually sending the cavalry into attack. But the day ended with the Allied forces being successful, and Ney pulling back to the farm where he had been that morning. He’d succeeded in stopping Wellington supporting the Prussian army though.

Wellington retired back to the village of Genappe and stayed at an inn for the night, waiting to hear from Lingy. 15,000 men had been lost.

At Lingy the fighting was just as fierce. With Napoleon’s cannon on the hills about the village, it was bombarded. When the French attacked, it is said in records, the bodies in the streets were two or three deep and blood ran about them. And the streets are wide, as you can see in my pictures below. A soldier described their entry to the village ‘When we reached the church our advance was halted by a stream and the enemy, in houses, behind walls, and on rooftops inflicted considerable casualties by musketery, grapeshot and cannon balls.‘

Another experienced soldier describes the terror of the scene, when he was used to battle, it had shocked even him. ‘A vast number of corpses, both men and horses, were scattered about, horribly mutilated by shells and cannon balls. The scene was different from the valley where almost all the dead preserved a human appearance because cannister, musket balls and bayonets were practially the only instruments of destruction used there…‘ I shan’t write the contrast of the scene he then added about the slope, it is a horrible description of what happens to men and animals hit by cannon fire.

The battle ended with the Prussians making a last stand at the point where this property stands. Blucher himself at one point came to make another push, and fell from his horse, but his men covered him with a cloak so the French would not recognise and target him, and got him out of there. The Prussians had been fighting over Lingy all afternoon and evening and ground in the village had been lost then won back over and over again, and no help had arrived from Wellington because his troops were trapped at Quatre-Bras trying to keep the crossroads open so that Blucher could use them if needed. It was then the Prussians realised that with the position of the village in the dip, and Wellington’s cannon on the hill, they would never permanently hold the village, it was better to let it go, and so with 16,000 men lost, and 8000 deserters, the Prussians withdrew.

An eyewitness account describes their faces as black from the gunpowder smoke, and layered with dust, while their uniforms were ripped, revealing skin where they had crawled through hedges to get away.

While Blucher recovered from his fall, Gneisenau, his Chief of Staff took over command, and an eyewitness describes the chaos as the army regrouped having fled. ‘I found him in a farmhouse. The village had been abandoned by its inhabitants and every building was crammed with wounded. No light, no drinking water, no rations. We were in a small room where an oil-lamp burned dimly. Wounded men lay moaning on the floor. The General himself was seated on a barrel of pickled cabbage, with only four or five people gathered about him. Scattered troops passed through the village all night long, no-one knew whence they came or where they were going… but morale had not sunk. Every man was looking for his comrades so as to restore order.’

So Napoleon had won one battle at Lingy as the sun rose on the 17th of June 1815, and when the Prussians regrouped, they decided to take a route,away from the main road to avoid Napoleon, and join Wellington. Luckily for them the French did not follow, they saw the 8000 deserters walking on another road, away from the fight, and believed that the Prussians were walking away from the war.

And Wellington had won the battle for the precious crossroads, but now the crossroads led to Napoleon, they were no longer precious. The Allied forces spent their night sleeping on the ground around the crossroads, attending their wounded. Then in the morning Wellington held on, waiting for word from Blucher, waiting to hear if the Prussians had won or lost. The scouts came back with the bad news, and so having loaded the wounded on to carts, Wellington made the decision to withdraw, he would let the crossroads go, and move to defend the road at Mont St Jean where a fork in the road, and the terrain, allowed Wellington the opportunity to fight defensively in his favourite formation and funnel the French into the assault his army planned.

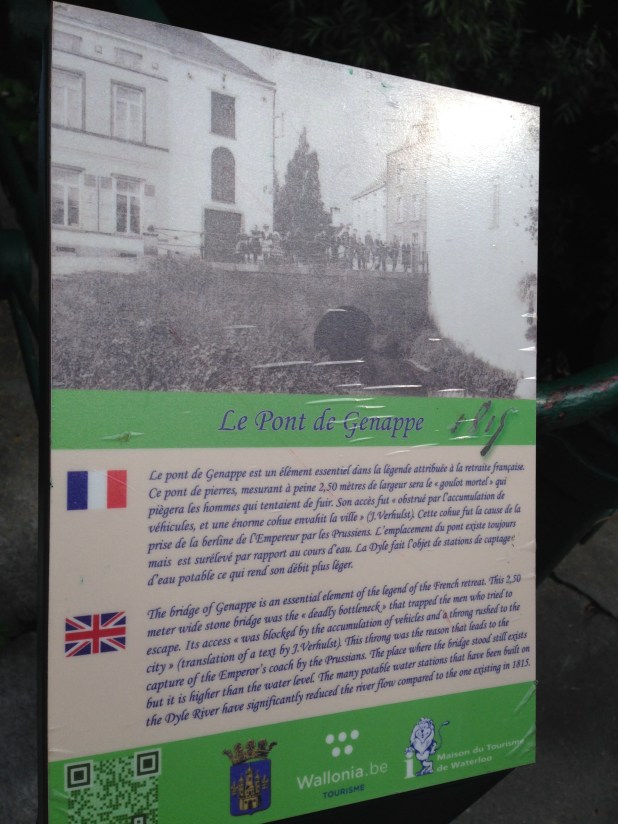

They spent the day of the 17th, pulling back, and Wellington had 30,000 men and 70 cannons to move a long a single narrow road. The carts full of the wounded were sent first, and then the artillery followed. The cavalry were kept at the rear with the light artillery, the riflemen, who would defend the retreat. It took just as much skill as a battle to manage a withdrawal. The land along the road undulated every 500 yards, and so cannon could be pulled back and fired, and then pulled back again, defending the retreating forces. The worst point was the bridge in the middle of the village of Genappe, which created a bottle neck for the cannon to pass through.

That night, the night of the 17th of June, a storm hit, that was described like a tropical storm the rain fell so hard, in torrents.

This is very battle based, and yet I had to learn all of this for Paul’s perspective in The Lost Love of a Soldier and it was so moving to walk about the places where things occurred, I wanted to share the details here. Being there gave me an understanding I hadn’t had before.

If you would like to read my fictional story set around the lead up to the Battle of Waterloo, then now is the time to do it, Harper Collins have put on some amazing deals this month to commemorate the battle. In one country the deal only lasts two weeks, though, I have not put the amounts as they are different in different countries, just click on the cover of The Lost Love of a Soldier in the side bar to find out your great cut price deal.

If you would like to see all the pictures and videos of Waterloo 200 which I will share on my Facebook page, click Like on the Jane Lark Facebook link in the right-hand column.

Look at all the book covers in the side bar to see the fictional stories I write… especially the limited time offer for Magical Weddings, which contains my story, The Jealous Love of a Scoundrel.