William Shakespeare died over 400 hundred years ago and yet today most people know who he is and where he came from, not only in the UK, but across the English speaking world and beyond. Why?

Earlier this year, I decided to visit Stratford upon Avon, birthplace and home of young and old William Shakespeare, a preserved treasure of Tudor England. I didn’t actually stay in Stratford Upon Avon for the Shakespeare experience; I am a life-time member of the National Trust and there are lots of historical properties to visit locally, as well as the town being a lovely place to stay with lots to see without having to get in a car. And, you know me, I love a historical setting – so the prefect place for a little holiday. I have so much to say about Stratford upon Avon my mind is brim-full with blogs and I’ve been holding on to them for ages and not had the time to write them up. But it means I am going to have to be careful to get my dyslexic/dyspraxic brain to stick to one theme per blog and not take you down lots of different, muddled rabbit holes.

So for today, I am going to answer the above question, an answer I discovered during in my stay, and was really surprised by because I’d assumed that Stratford upon Avon was a destination place from Shakespeare’s lifetime onwards. No …

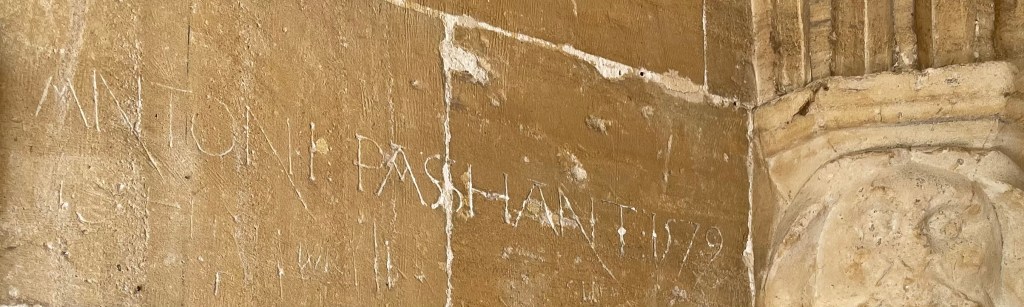

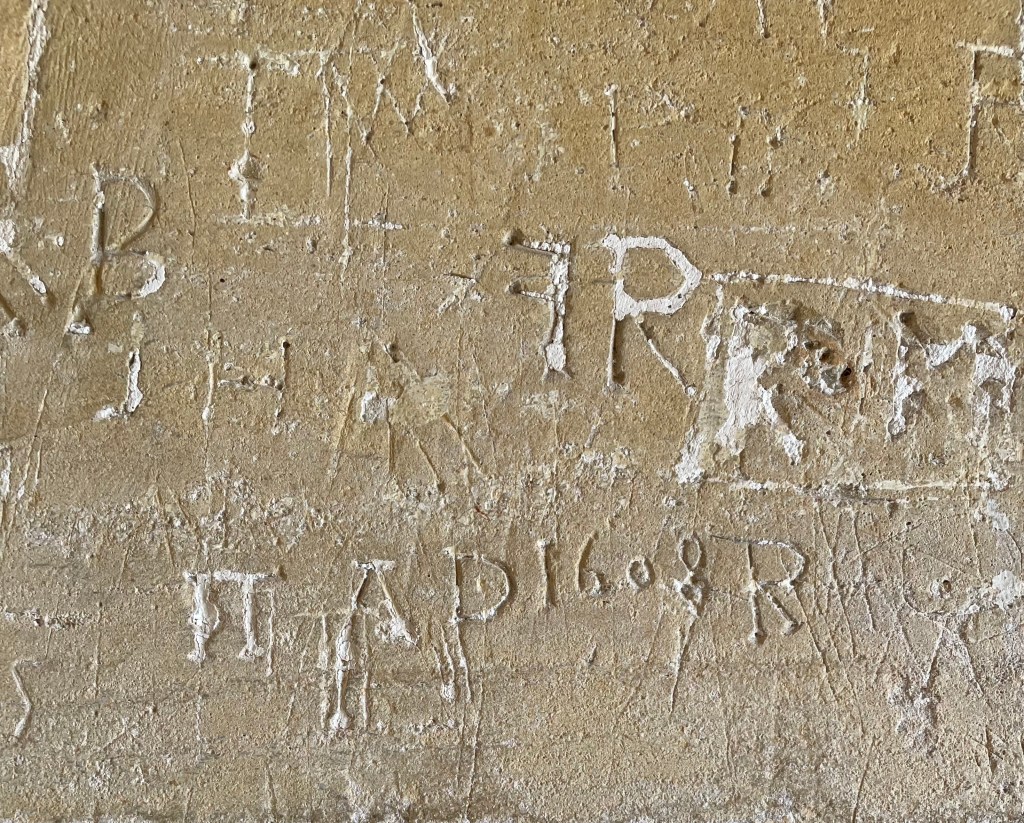

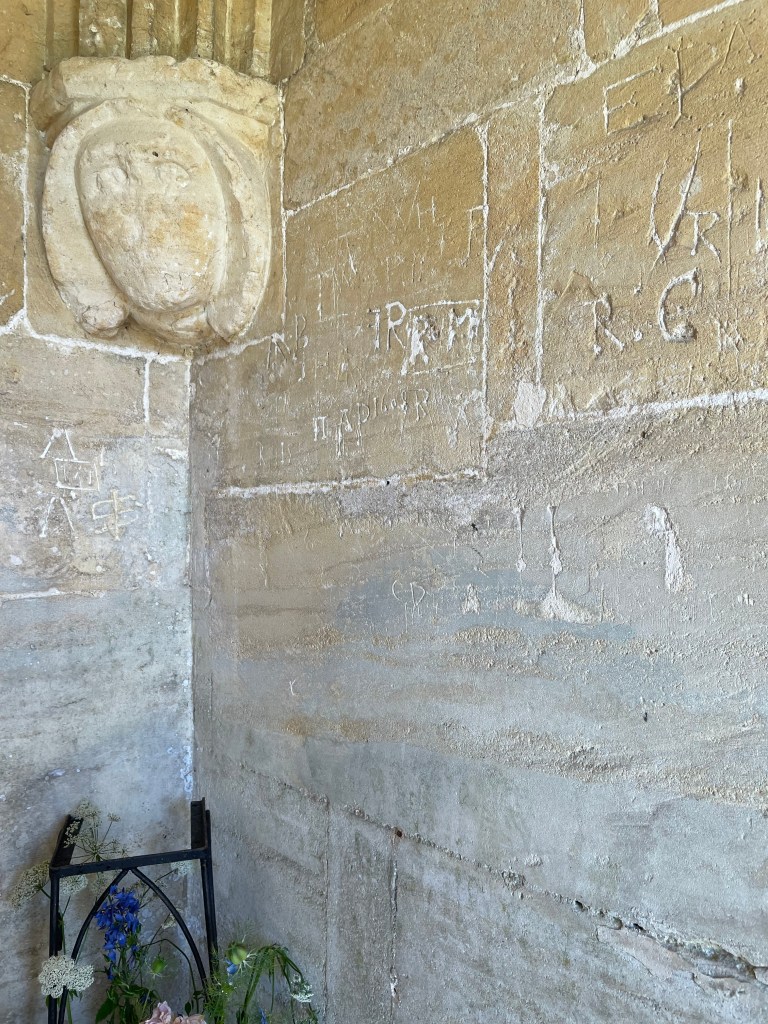

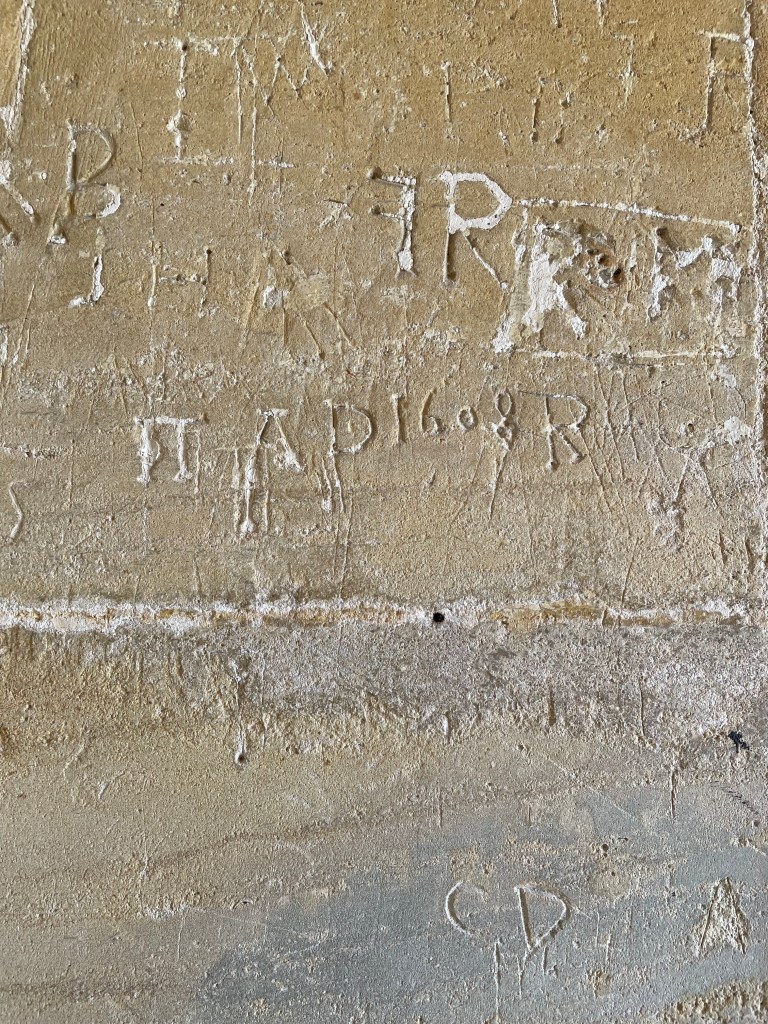

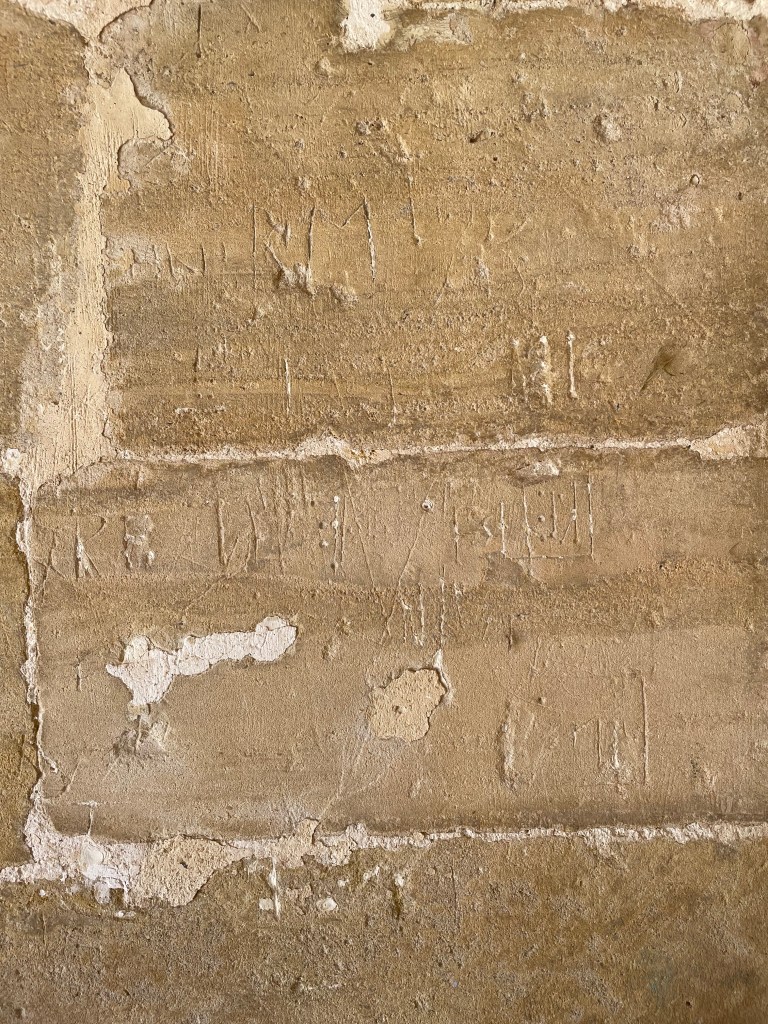

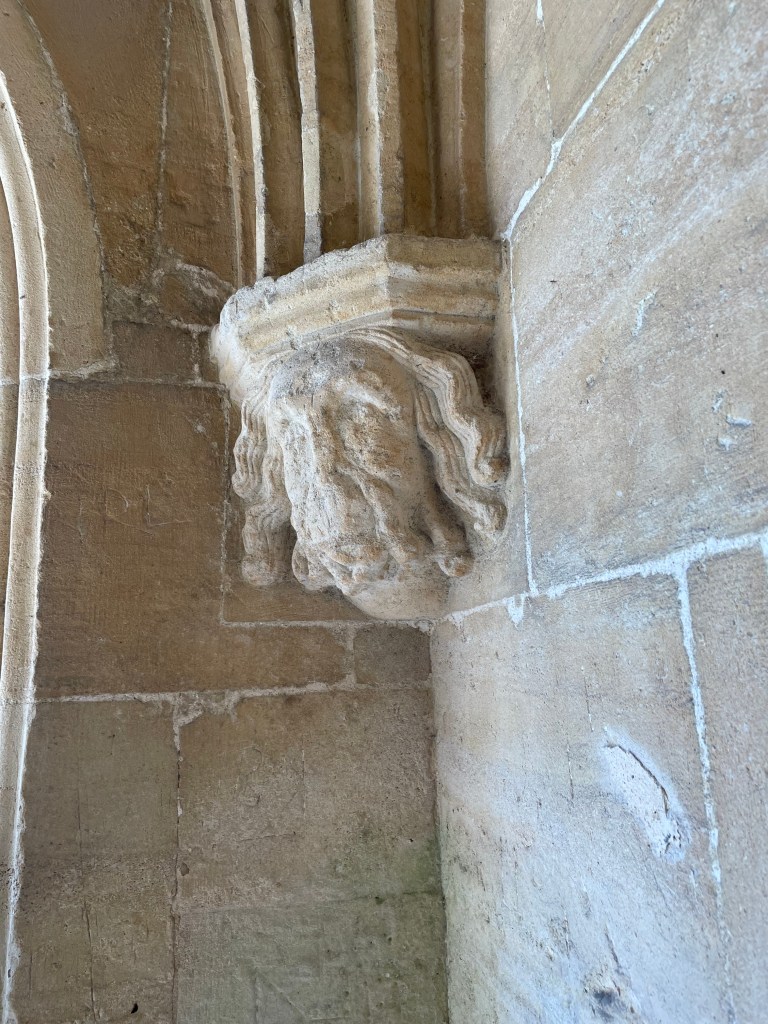

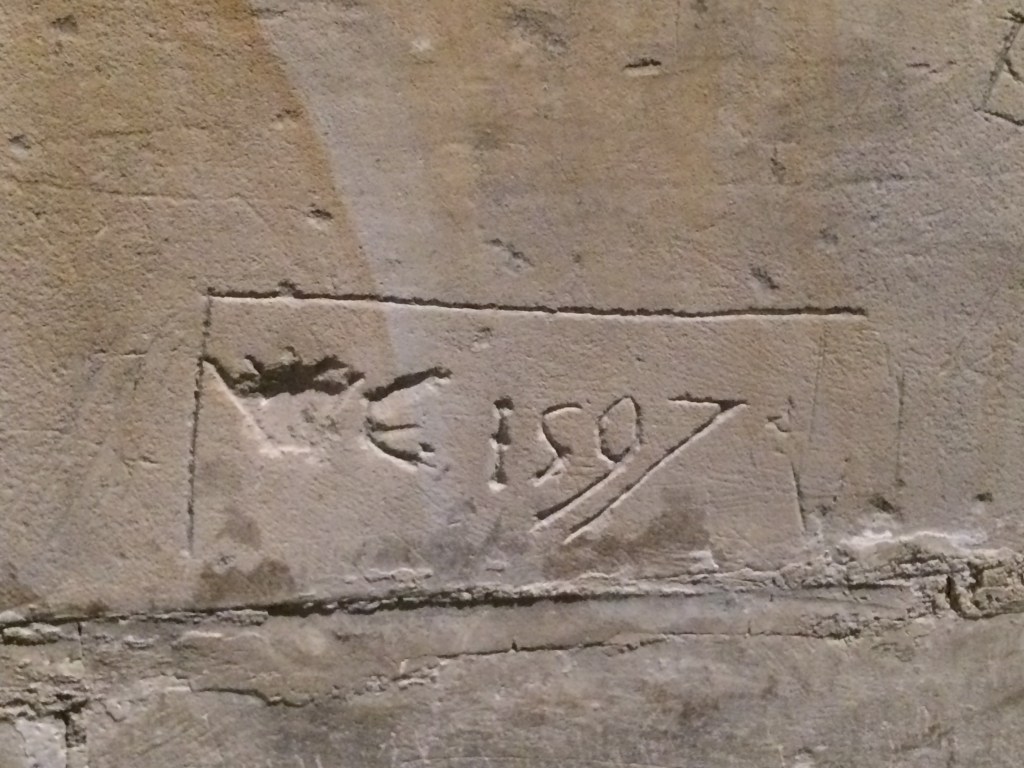

The first hint that there was something I didn’t know about the history of the pilgrimage Shakespeare’s fans make, references my last post including my fascination with graffiti. On the first day of our stay, we walked along the bank of the river Avon and came across Holy Trinity Church where Shakespeare is buried, and was baptised.

Before we entered the church I spotted on the riverside wall a lot of graffiti. It’s actually very unusual to see historical graffiti on the outside walls of a church. I’ve never seen it before… My husband and I, however, noticed that a lot of carvings were from the 1800s onwards. This was also unusual.

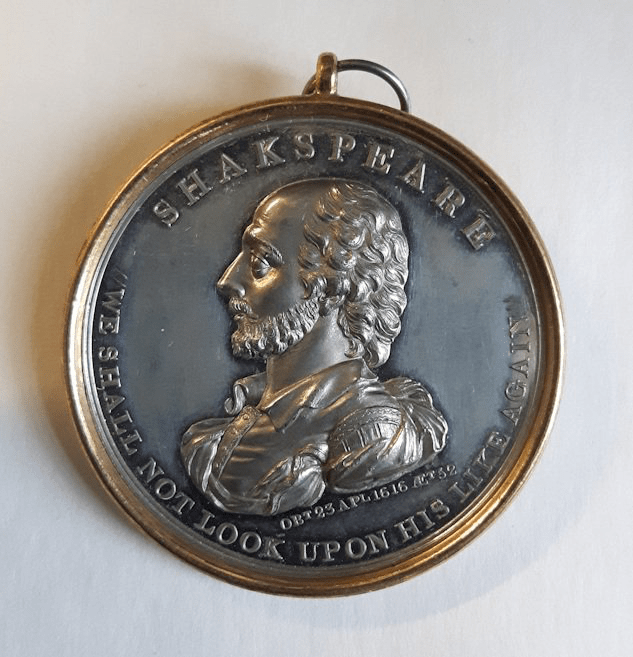

Then I read about the Shakespeare Jubilee established by David Garrick, a successful and famous actor in Georgian England. https://www.shakespeare.org.uk/explore-shakespeare/shakespedia/david-garricks-shakespeare-jubilee/. “In 1769, David Garrick threw a party that put Stratford-upon-Avon on the map as a tourist destination for Shakespeare fans.”

Shakespeare’s birthplace had not been celebrated until David Garrick put it on the map as a place to be seen. Though, his idea failed at the time – an outdoor display of theatre was washed out by the weather. But his initial desire was followed through as King George III was succeeded by his son as Prince Regent who became King George IV. In the Regency period of ‘romantic’ fashions what could be more romantic than treasuring the man, Shakespeare, who created such wonderfully romantic and powerfully dramatic works!

While Garrick’s original festival was a bit of a disaster, the idea stuck. He used the material of his planned celebration in theatres across Britain and Europe and then… “In 1816 Stratford held an organised commemoration of Shakespeare’s death for the first time. The festival was closely modelled on Garrick’s Jubilee and was organised by the sons of those committee members who had been involved with it,” and, “In 1824 the Shakespeare Club was founded in Stratford.” This, therefore, alluded to why so much of the graffiti on the church wall of Shakespeare’s burial place came after this era. “Three years later the 1830 Jubilee attracted nationwide interest and even received Royal Patronage.”

Stratford upon Avon then became one of the most ‘romantic’ and ‘fashionable’ places to visit. Celebrities of the time, all the romantic poets, are recorded as visiting the town in the 1800s. It became a pilgrimage destination for writers and painters alike.

What I think is particularly wonderful about this adulation for Shakespeare’s home town that began in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, is that it meant Stratford upon Avon was saved from being completely dressed in Georgian architecture. What I mean by this is shown in the town where I live…

The Castle Town of Devizes, like many towns in Britain, in appearance is full of properties built in the Georgian period…

But behind the scenes…

Because the Georgians, in the 1700s, travelled the world, and were inspired by European architecture, they wanted their properties in our towns to look like the grand places they’d seen in Europe – resembling Roman and Greek buildings. They wanted the outside of their properties to be an architectural artwork, with blind pilasters, balustrades and carvings. Of course, rebuilding would cost a lot of money, so often, the Georgians just built a new front wall, literally face-painting our medieval towns. This is most apparent in the pictures top left in the above two galleries, the wooden framed walkway is behind the front door of Parnella House in Devizes marketplace. But because Stratford upon Avon was being celebrated for its historical beauty in remembrance of Shakespeare’s life, the Georgians restrained this desire and left much of the Tudor and earlier architecture untouched…

So, we have David Garrick’s 18th century failed jubilee and then Stratford upon Avon town Corporation’s investment in continuing this theme, and lastly those who established Stratford’s ‘Shakespeare Club’ in 1824, to thank for preserving the historical buildings in the town, and for it’s recognition as the home town of Shakespeare. That is why so many people still visit Stratford upon Avon today.

“In the words of Mrs Hart – a descendant of Shakespeare and one time custodian of Shakespeare’s Birthplace, ‘People never thought so much of it till after the Jubilee’.”

Quotes taken from – https://www.shakespeare.org.uk/explore-shakespeare/shakespedia/aftermath-jubilee/

There’s lots more for me to say about the things I discovered, and the places I visited in and around Stratford upon Avon, so follow my blog if you don’t want to miss a post.