If I could pin down a point in time when I first became fascinated by historic graffiti it might be the first time I saw the wall carvings in The Beauchamp Tower, in The Tower of London. I remember scanning it for ages. Some well known prisoners and lesser known prisoners were locked up in The Beauchamp Tower for years at a time during the reigns of King Henry VIII and Queen Elizabeth I. Of course, the amount of days they had time to pass means some of the graffiti is very detailed.

It was one of those moments that made me stop and think about the individual – the human – who had worked on the image with a knife in their hand carving out every detail for hours, standing or sitting in exactly the same space I was hundreds of years before me. Being a storyteller, my mind immediately leaps to trying to get into their minds. What were they thinking as they worked? How did they feel at the time?

Anyway, ever since then, I hunt for historic graffiti where ever I think it’s likely I’ll see it, and if you’ve followed my blog for a while you will have seen me post about it when I do find it. Cathedrals are great for graffiti, around the choir stalls and in any other areas where people would have stood for some time. On the backs of pillars in the nave and in all sorts of areas outside the central nave. My husband is now as fascinated as I am and we usually try and find the oldest mark as people mostly write the year and their name or initials. You will not find very much on the normal pews though, pews were quite a late addition to churches and cathedrals the nave was originally an open standing space.

Ruins are another great place for historical graffiti, castle ruins, or follies in gardens. This usually dates from the Georgian, Regency or Victorian periods or later. These are places were people would have visited with others and perhaps talked to one another as they carved. These carvings are mostly in soft stone work, like the sandstone used in Georgian buildings, because people did not have years to carve and were tempted by an easy target.

But anyway, this post is really about a particular piece of graffiti my husband spotted in a church porch in a village just down the road from us.

You may remember that a while ago I did a lot research to try and find out how old my house is. You can find those posts on the Index page under the heading ‘The History of a House on an English Village Green’ .One of the owners I discovered, who owned this land and quite a few local manors and their land from 1597, was a clothier called Edward Long. From what I can tell he bought all the manors to own the land to rear sheep. None of the family lived where our house is. Their main place of residence was in a village a short way down the road from us, in Steeple Ashton, it would have been known only as Ashton originally.

So, when we had nothing to do one day recently, I said to my husband, ‘Can we go and look at the church in Steeple Ashton?’ I know the Longs had a lot of money at the time, their names are still used in lots of places near us, in pubs and village names, and I wanted to see if the family graves were in the church. When we walked up to the church I was very surprised to see something very different from an average village church.

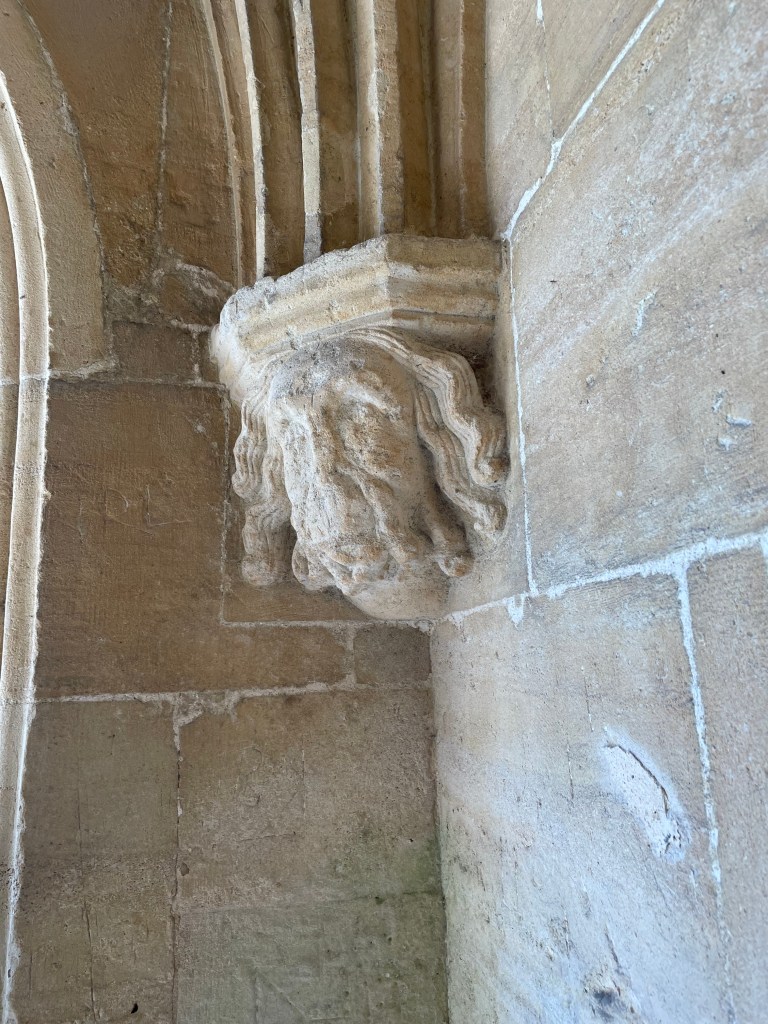

Steeple Ashton Church is unlike most churches that are predominantly medieval, it is Tudor. A Tudor church. There is a contemporary record of the church being built in the Tudor period, ‘When Leland visited Steeple Ashton c. 1540 he remarked that ‘it standithe muche by clothiars’ and named two, Robert Long and Walter Lucas, who had assisted in the building of the parish church.‘ At the time the church had a notably tall steeple but the steeple fell when it was hit by lightning not long after it was first built.

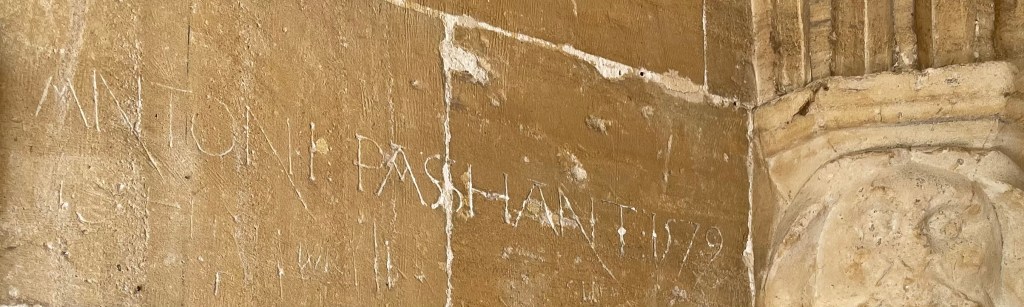

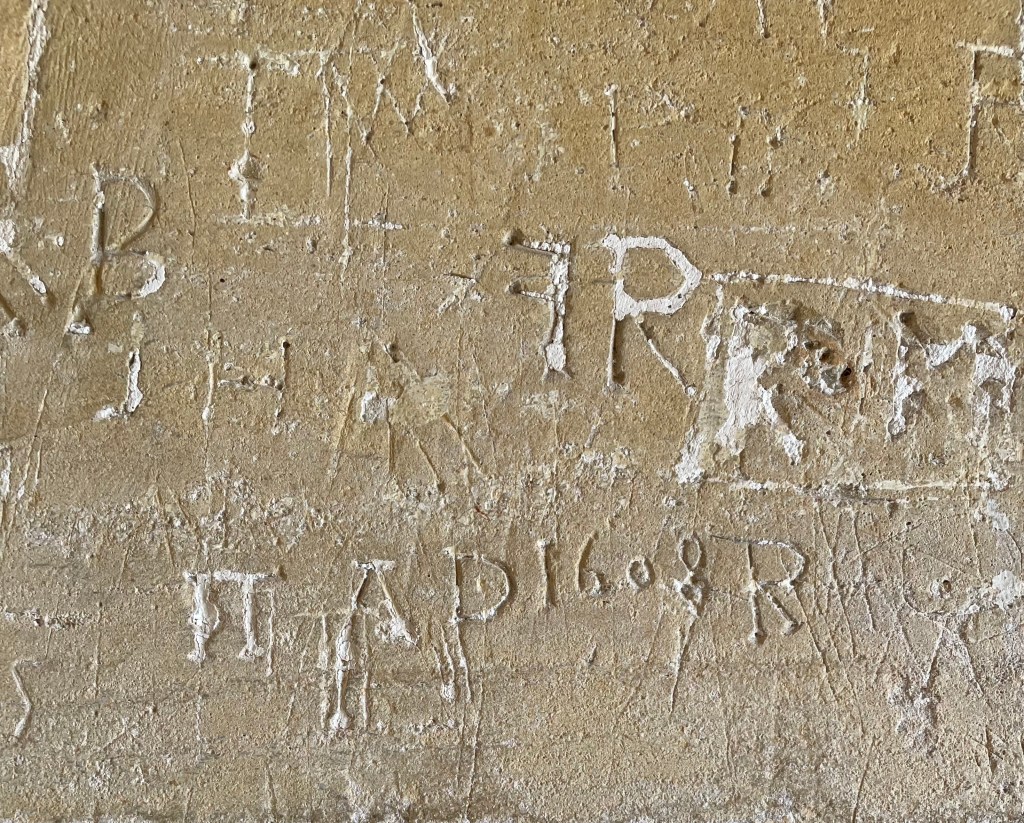

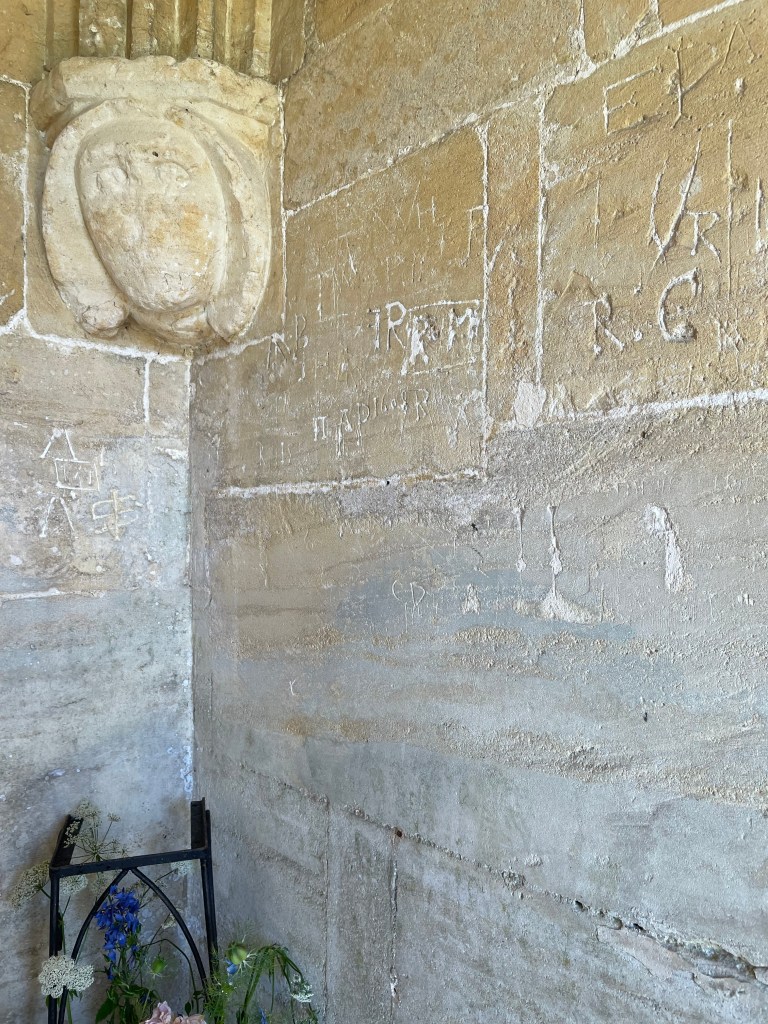

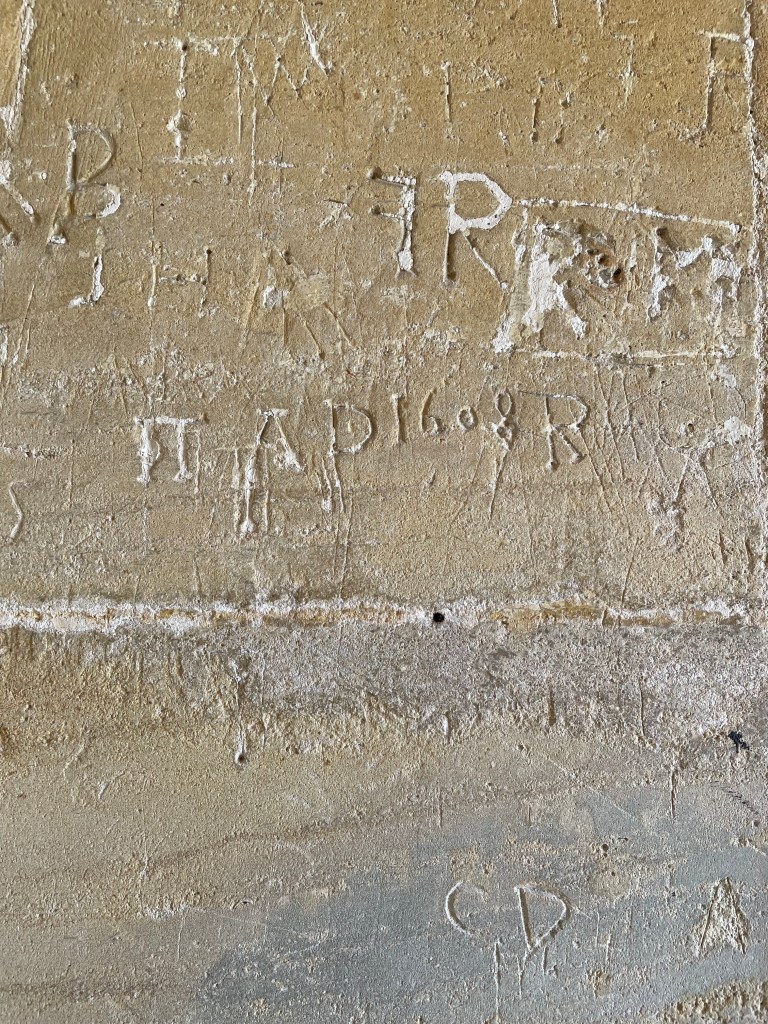

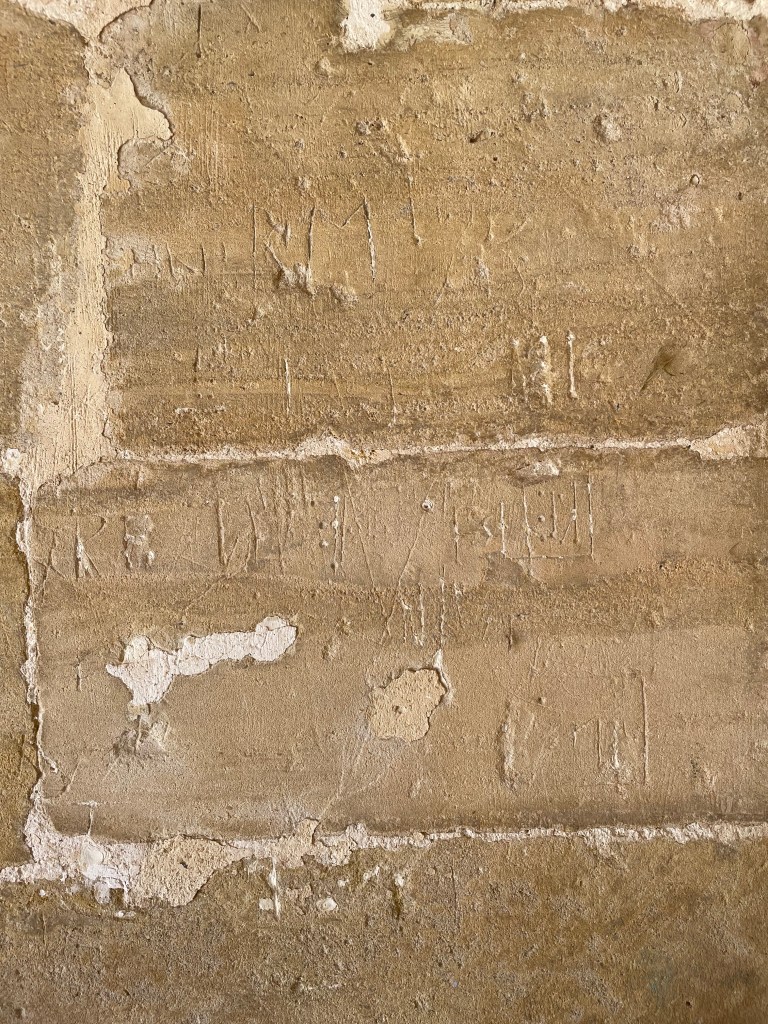

Another difference was that churches rarely contain graffiti. Perhaps because they’ve been continually used by local people who want to keep their church smart, they would have removed graffiti at the time, as we’d remove it today. Or perhaps because churches are smaller people can’t hide for long enough to carve. But anyway, here is where Steeple Ashton Church is different again, because I started noticing some graffiti in the church porch, and then… My husband spotted one of the oldest pieces of graffiti we have seen. 1579. Certainly the oldest piece we’ve come across by accident.

Graffiti in Steeple Ashton Church Porch

In 1579, when Antoni wrote his name on this wall, Queen Elizabeth I was on the throne, and still relatively young. Shakespeare was alive and writing his plays. Raleigh was sailing around the world discovering other lands and plants previously unknown in Britain.

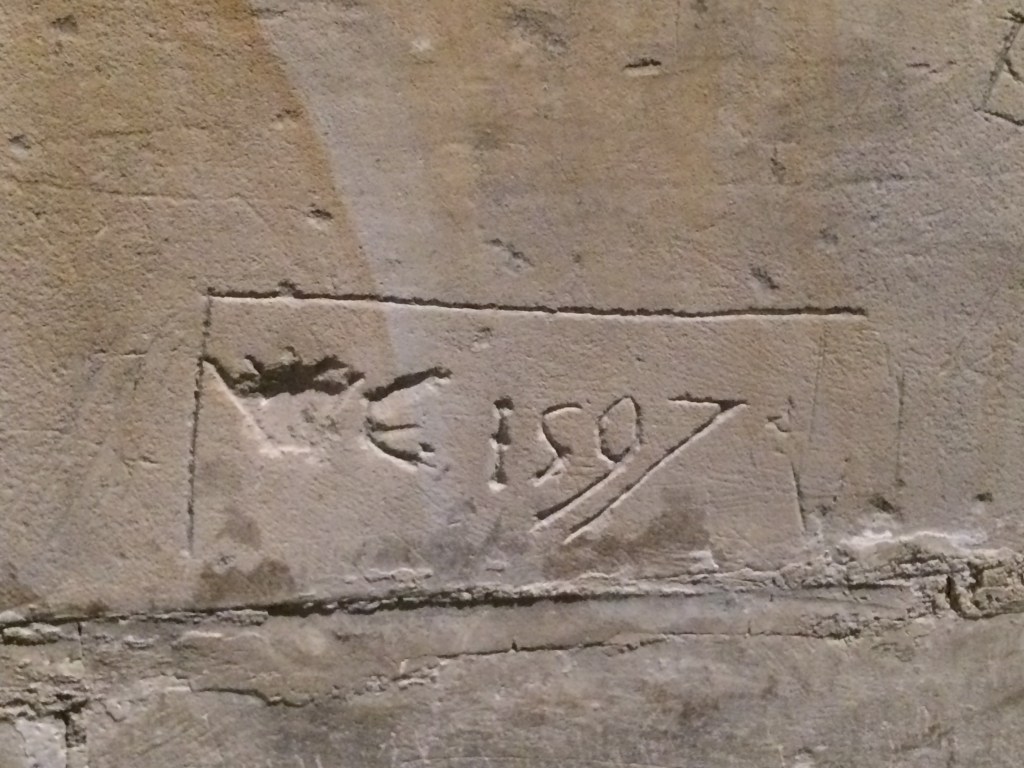

Interestingly, in my heading images, is another piece of graffiti we spotted dated to the 1500s. This was in Canterbury Cathedral. It’s interesting that both 7s and 9s are carved with long tails which must have been the style of writing then.

Graffiti in Canterbury Cathedral

So we have found an earlier carving by eighteen years. Fascinating.

If I can find out anything about Antonio Passhant, I will tell you more one day. But I am just so excited that after all these years of searching historic graffiti, the oldest, well with a date anyway, is about fifteeen minutes away from where I live!