I would love to begin a great big shout out of gratitude to the railway workers in the UK in WWII. In the same year we celebrate ‘Railway 200’ marking the invention of the steam train, and 85 years since the evacuation of troops from Dunkirk and other beaches, why do people still not know about the role the railway companies and workers played in saving so many men?

The railways played as important a part as the small boats, and this is where we realise the influence of propaganda on history.

Shouting about the involvement of the small boats, was a good way of showing Hitler and his military staff that Britain would rally, that the British were resilient and civilians would stand together to fight and save each other. Where as, when it came to the involvement of the railways, they did not want the Germans to know where the soldiers who had been saved were, the did not want to risk the Luftwaffe bombing camps and killing our soldiers who the country had invested so much effort in saving. So, propaganda did not shout about the role of the railway workers, and history has therefore simply forgotten.

You generally don’t realise what you don’t know until you need that knowledge, and to write the second book in The Great Western Railway Girls series, I needed to know what happened on this side of the channel after the evacuations of the allied forces. The 85 years recognition happened this summer, and if you watched the documentaries about the evacuations, they all focus on what happened in Flanders and France and take you up to the moment the men find a route to get home on a ship or small boat. I wanted to know about what people did here and where the men went when they got home. My characters would not even have known what was going on abroad at that time, apart from what could be seen and heard from this side of the channel.

It took a lot of hunting to find out, and actually most of the information I found was shared by the women who supported the planning of the evacuation in England and helped the soldiers when they arrived in Dover. The press were mostly silent about what happened when the troops made it home.

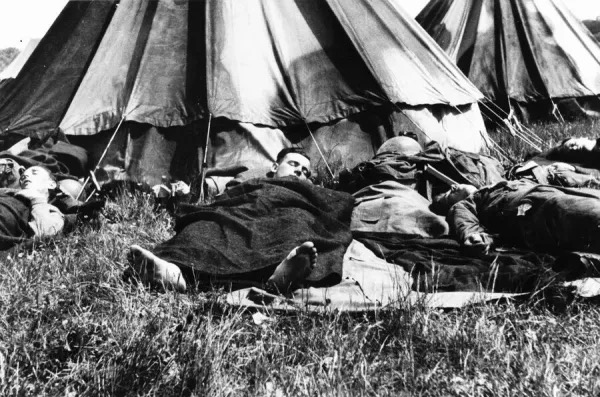

My first discovery, was a personal account from a WREN who had been working in the War Tunnels in the cliffs of Dover, helping to organise the evacuations, requisitioning boats and ships and planning the movements of those and the navy vessels. She wrote about coming out from the tunnels with colleagues, to go down to the harbour at Dover and help the men who were arriving. She said they arrived in a terrible state, some even completely naked, and most of them had neither eaten nor slept for days because the Germans had raced through France so quickly. They had been running for their lives for days, retreating to get to the coast without being killed or captured by the Germans, with no time for rest.

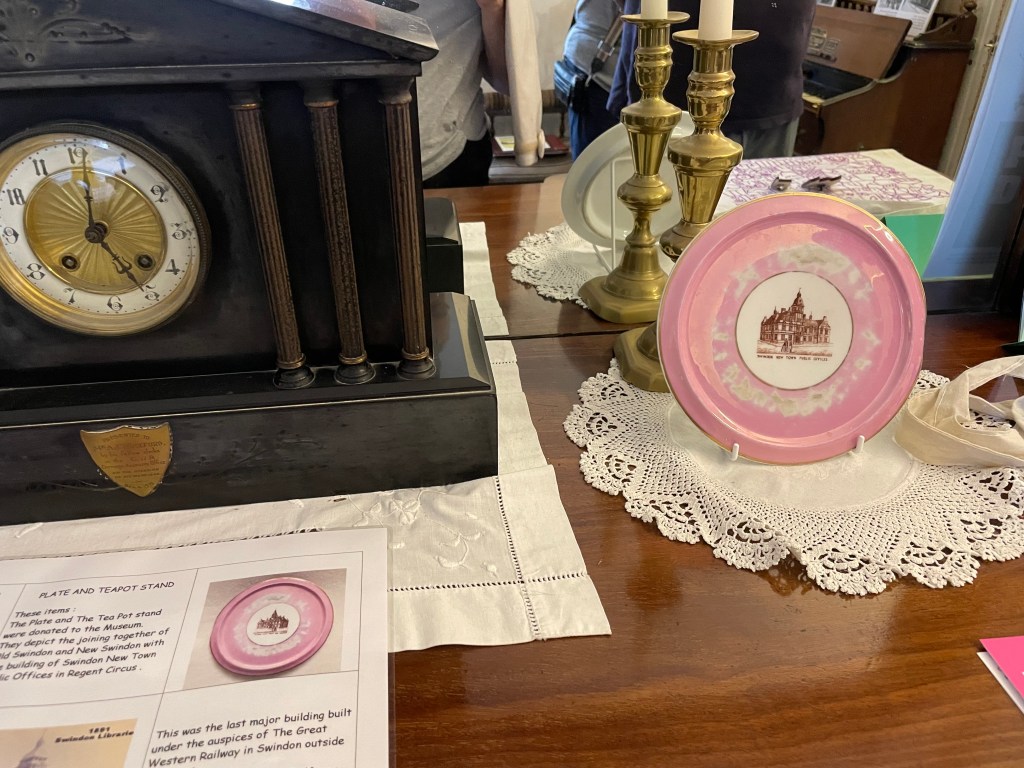

It was in a 1940 GWR company magazine in Swindon’s STEAM Museum records that I began discovering the role the railways played. All the British railway companies were involved in the planning of Operation Dynamo which was done in a matter of a few days. Every train in the country and every trainline was involved in getting as many carriages to Dover and away from Dover as quickly as possible, then returning with cleaned carriages to collect another load of men. This included hospital carriages to move the wounded as well as normal carriages which were packed full using every inch of space.

It was as important to get the men away from the English coast as it was to remove them from France, otherwise they would have been sitting ducks for the Luftwaffe to fly over the channel and end what they had begun on the other side.

In those few days of planning, camps had been set up all over the country to receive the men, at locations that were kept secret. I discovered one of those was close to Swindon, at the army camp near Chiseldon. However, I don’t describe Chiseldon camp in the book, The Great Western Railway Girls Do Their Bit, because Chiseldon camp had a railway station and I’d read a more dramatic option. I found a personal record from a woman who was helping out in a camp who said that the men had to march five miles from the station to the camp, in the condition they’d arrived at in Dover. It was miraculous really that they were able to do it, and I wanted to put this in the story.

You should also remember, The Government’s plan had an expectation of saving around 35,000 men. They had therefore planned to move 35,000 men on the railways and receive 35,000 in the camps. But their plans had to ramp up several gears in a matter of hours when the plans were put into action, and the men returning flooded into Dover, 350,000, ten times the number they’d planned to process at the port and move in land.

The GWR magazine recorded that on one day alone during the period of the evacuations from France, 200 trains ran out of Dover, moving the men away from the port, which meant that many staff had to volunteer to do jobs on the trains they were not normally involved in…

All great information for me to be able to write my characters into these events.

But why are we in the year of Railway 200, and 85 years since Dunkirk, not telling the story of the part the railways played in saving hundreds of thousands of men. So whenever you have opportunity, tell others and get the story out there!

Images are subject to copyright, used with agreement of the copyright owner or with payment.

Learn more about The Great Western Railway Girls novels here -> The Great Western Railway Girls