The assembly rooms in Bath had their heyday in the 1700s. I say assembly room’s’ because there were three in Bath, which was a popular social retreat of the time. The Bath season ran from October to June, and occupancy of Bath increased from 3000 in 1700 to 35,000 in 1800. Jane Austen’s first visit to Bath was in 1797 and it is after this visit she wrote the first draft of Northanger Abbey which includes descriptions of assemblies in the Upper Rooms.

The assembly rooms in Bath had their heyday in the 1700s. I say assembly room’s’ because there were three in Bath, which was a popular social retreat of the time. The Bath season ran from October to June, and occupancy of Bath increased from 3000 in 1700 to 35,000 in 1800. Jane Austen’s first visit to Bath was in 1797 and it is after this visit she wrote the first draft of Northanger Abbey which includes descriptions of assemblies in the Upper Rooms.

The New Rooms or the Upper Assembly Rooms were completed in 1771. They were considered necessary as the two other assembly rooms were thought old fashioned, too small for the crowds which now flocked to Bath and too far from the now more fashionable areas of Bath, the Circus and the Crescent. The other assembly rooms were originally Harrisons (later Haye’s, Hawley’s and then Simpson’s which was built in 1708) and Lindsey’s (later Lovelace’s and then Wiltshire’s designed in 1728). Some of these various proprietors were women.

These assembly rooms provided visitors with a number of entertainments, dancing, card playing, music, theatre, billiards and refreshments. Harrison’s also had gardens where patrons could walk and take tea. However once the New or Upper Rooms opened, on the 30th September 1771 at 7 o’clock, both Simpson’s and Wiltshire’s suffered, Wiltshire’s soon closed and Simpson’s burnt down in 1820.

At the time the upper rooms opened it cost ‘One Guinea to admit One Gentleman and two ladies at seven shillings each.’

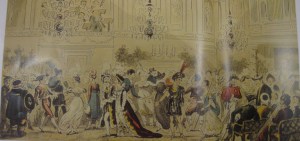

An ‘assembly’ was described in 1751 as ‘a stated and general meeting of the polite persons of both sexes for the sake of conversation, gallantry, news and play’. Festivities in the Upper Rooms included a Dress Ball on Mondays, a Concert on Wednesdays and a Cotillion Ball on Thursdays. However the rooms were open every day for people to walk and play cards. Each room had a main purpose a Ball Room, Card Room and Tea Room, but their uses did vary.

The Ball Room as described in 1772 is ‘105ft 8in long’ and in the 18th Century it would have been packed with 800 dancers. Between 6-8 the 11 musicians who sat in a first floor balcony played minuets. A stately dance for couples. ‘It is often remarked by Foreigners that the English Nation of both sexes look as grave when they are dancing, as if they are attending the solemnity of a funeral.’ However more energetic country dances followed between 8-9, until refreshments were provided, and again after refreshments when country dances continued until 11. The term country dances comes from the French ‘contra-dance’ describing the fact that these dances commenced with one line of gentlemen facing a line of women, the pairs and lines then danced in a variety of patterns. The dancers were observed by others at the edge of the room talking, flirting, walking or seated on a three tiered structure.

The Ball Room as described in 1772 is ‘105ft 8in long’ and in the 18th Century it would have been packed with 800 dancers. Between 6-8 the 11 musicians who sat in a first floor balcony played minuets. A stately dance for couples. ‘It is often remarked by Foreigners that the English Nation of both sexes look as grave when they are dancing, as if they are attending the solemnity of a funeral.’ However more energetic country dances followed between 8-9, until refreshments were provided, and again after refreshments when country dances continued until 11. The term country dances comes from the French ‘contra-dance’ describing the fact that these dances commenced with one line of gentlemen facing a line of women, the pairs and lines then danced in a variety of patterns. The dancers were observed by others at the edge of the room talking, flirting, walking or seated on a three tiered structure.

Jane Austen describes the commencement of an evening in the ballroom in a letter dated 12th May 1801, ‘Before tea it was a rather dull affair; but then before tea did not last long, for there was only one dance, danced by four couple. Think of four couple, surrounded by an hundred people, dancing in the upper Rooms at Bath! After tea we cheered up; the breaking up of private parties sent scores more to the Ball and though it was shockingly and inhumanely thin for this place, there were people enough I suppose to have made five or six very pretty Basingstoke assemblies!”

The Ball Room was clearly busy in 1771 however, as rules established at the time insisted women were not permitted to dance the country dances wearing hoops, due to lack of space, a separate room was made available where serving maids assisted ladies who wished to dance in removing their hoops.

Refreshments were served in the Tea Room, which was also the room used for concerts. This location was used in the 2009 film ‘The Duchess’ in the scene where Georgiana is introduced on the balcony in Bath, and in the 2007 version of ‘Persuasion’ When Anne attends a concert which she has encouraged Frederick Wentworth to attend.

Refreshments were served in the Tea Room, which was also the room used for concerts. This location was used in the 2009 film ‘The Duchess’ in the scene where Georgiana is introduced on the balcony in Bath, and in the 2007 version of ‘Persuasion’ When Anne attends a concert which she has encouraged Frederick Wentworth to attend.

Meals were served in the Tea room throughout the day from ‘public breakfasts’ onwards, but during balls a buffet was laid out on side tables, including ‘sweetmeats, jellies, wine, biscuits, cold ham and turkey.’ Jerry Melford’s depiction of the point when the bell rang to announce supper during a tea party in Humphry Clinker is not perhaps as we might imagine genteel society dining. ‘The tea-drinking passes as usual, and the company having risen from their tables, were sauntering in groupes, in expectation of the signal for attack, when the bell beginning to ring, they flew with eagerness to the dessert, and the whole place was instantly in commotion. There was nothing but jostling, scrambling, pulling, snatching, struggling, scolding and screaming.’

Jane Lark is a writer of authentic, passionate and emotional love stories.

See the side bar for details of Jane’s books, and Jane’s website www.janelark.co.uk to learn more about Jane. Or click ‘like’ on Jane’s Facebook page to see photo’s and learn historical facts from the Georgian, Regency and Victorian eras, which Jane publishes there. You can also follow Jane on twitter at @janelark