A taster;

‘Every day at Longbourn was now a day of anxiety; but the most anxious part of each was when the post was expected. The arrival of letters was the first grand object of every morning’s impatience. Through letters, whatever of good or bad was to be told would be communicated, and every succeeding day was expected to bring some news of importance.’ Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen.

As Jane Austen says letters were the only form of communication beyond verbal interaction in the 1700 and 1800s and therefore transport was pivotal.

This last story springing from the old Theatre Royal Bath will tell a little more about an actors/actresses life in the 18th and 19th Century and how they travelled, and how this then affected the establishment of a postal service with reference to Jane Austen’s experiences as recorded in Pride and Prejudice.

Once John Palmer had successfully transformed the Theatre Royal and established entertainments to rival London’s Drury Lane and Covent Garden, he was not satisfied to simply sit back and glory in his success, he turned his eyes on Bristol, fifteen miles further South. Bristol was a busy port then and a hub of international business. Consequently it could support another high calibre theatre. John Palmer leased a theatre in King Street in 1778 and then used this to help him in developing the quality of the shows in Bath and Bristol by offering theatre companies shows in both venues, to double their income. They would literally play back-to-back shows; perform in Bath and then race off to Bristol to perform again and vice versa.

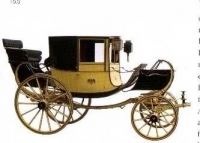

To enable this he needed to not only be able to transport actors and actresses between the venues but also stagehands and props. To do this in the speed he needed he ran a daily coach between the venues pulled by four horses.

There is a fascinating quote from the actress Sarah Siddons, who I discussed in my last blog, describing this hectic acting life;

‘After the rehearsal at Bath, and on a Monday morning, I had to go and act at Bristol on the evening of the same day; and reaching Bath again, after a drive of twelve miles, I was obliged to represent some fatiguing part there on the Tuesday evening. I wonder that I had strength and courage to support it, interrupted as I was by the cares of a mother, and by the childish sports of my little ones, who were of the most unwillingly hushed to silence from interrupting their mother’s studies.’

One of my abiding themes when I think and write about characters from history is that they lived in a different time, with a different way of life to support them but within themselves they were the same as us. Human thoughts and human feelings are unchanged going right back to certainly beyond the medieval era. Life about them may have set different boundaries for wrong and right, but they still felt, joy, fear, courage, uncertainty, pain, love, infatuation, hardship, embarrassment… The list is endless. However even I am surprised to discover a woman expressing the views any working mother might feel today and especially an actress.

When I think of actresses in the 1700s and 1800s I think of the green room where they entertained wealthy adoring men following their performance, I did not imagine a woman surrounded by young children clamoring for attention, “Look at this, Mama.” “Pick me up.” And yet the quote above describes a life like that. When Sarah first began performing in the Bath and Bristol Theatres she was married with two young children and her children were part of the reason she made the decision to settle at Bath because she no longer wanted to continue touring in a Theatre Company. This was what most actors and actresses did, changing towns frequently to establish a new audience and acting in halls and barns.

I shall not put a picture in of Thomas Rowlandson’s image of a theatre dressing room, which is more inline with my previous view, it’s a bit rude, but here’s the link if you’d like to see it,

How many mothers today choose to change from a job which makes it harder to be a parent? Many of us I’m sure. And then you can imagine she took them with her in the carriage as she learnt her lines travelling between Bath and Bristol and clearly from the quote above she felt guilty for telling them to be silent while she studied and mentally rehearsed. Now how many mothers feel like that? I have had a similar conversation regularly with my friends who are authors. ‘Childish sports‘, you can imagine them climbing all over the carriage and back stage, picking things up they should not touch and playing with them. It’s a fascinating concept to discover the same tribulations of a working mother written in the life of an 18th Century actress. She definitely did have the children in the theatre at times we know because there are records of her using the children as characters on stage at times.

Anyway, back to travel and John Palmers carriage. He used the same carriage to take him to London to visit the Theatre Companies there and bring actors and actresses back to Bath and he could do this journey in less than a day.

In comparison the mail system transporting letters at the time took three days for a letter to reach London if posted in Bath. The difference was because post was transported by single riders in a chain, a bit like a relay they would ride their stretch and then pass the post bag on to the next rider for the next stretch.

John Palmer took it upon himself to change this. He knew he could do it much quicker in a coach so he encouraged, not without resistance, for the mail service to be run by coach instead. William Pitt, Chancellor of Exchequer at the time, agreed to John Palmer funding his own trail. It took place in 1784 and it ran from Bristol to London. John Palmer’s coach racing the mail. Well it was hardly a race was it, the coach arrived in half the time and the Bristol to London Mail Coach Service was established. The same was implemented initially on four other routes and within a year these routes had tripled. In 1786 John Palmer became the Comptroller General of the Post Office and gave up managing the theatre’s, selling them on to his former manager.

Jane Austen used this postal service to exchange letters with her sister Cassandra during her life and describes this experience of communicating through letters in her books.

‘She was engaged one day as she walked in reperusing Jane’s last letter, and dwelling on some passages which proved that Jane had written in spirits.’ Elizabeth walks in Lady Catherine De Bourgh’s park and meets Colonel Fitzwilliam.

‘When they were gone, Elizabeth, as if intending to exasperate herself as much as possible against Mr. Darcy, chose for her employment the examination of all the letters which Jane had written to her since her being in Kent.’ Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen

‘Elizabeth opened the letter, and, to her still increasing wonder, perceived an envelope containing two sheets of letter-paper, written quite through, in a very close hand. The envelope itself was likewise full.’ Darcy hands Elizabeth his letter in Pride and Prejudice.

Many of Jane’s scenes in her books begin with or include letters and this only shows how pivotal letters were in peoples’ lives before phones and computers were invented. There is also Lydia’s letter to the family when she eloped and Mr Collins’s to Jane’s father explaining his opinion on the elopement. I think there was perhaps more emotion carried and poured in to letters and certainly when waiting for their arrival with expectation, excitement or concern and disappointment when they did not come. Everyone’s lives would have revolved in some way around these bits of paper and the feelings they engendered in the 1700 and 1800s, so when John Palmer introduced the faster postal service you can then imagine how precious a thing it was to be able to write a letter and know it would be received in half the time.

Think of the urgency of such letters as the one Jane sent to Elizabeth in Pride and Prejudice about Lydia’s elopement.

‘Elizabeth had been a good deal disappointed in not finding a letter from Jane on their first arrival at Lambton; and this disappointment had been renewed on each of the mornings that had now been spent there; but on the third her repining was over, and her sister justified, by the receipt of two letters from her at once, on one of which was marked that it had been missent elsewhere. Elizabeth was not surprised at it,a s Jane had written the direction remarkably.’ Elizabeth received Jane’s letter informing her of Lydia’s elopement.

Before John Palmer’s postal system it was often days before people knew either good or bad news and often far too late to have any affect on its outcome. Jane Austen must have received the news of her Aunt’s Mrs Leigh-Perrot’s arrest for theft in Bath with equal panic to the upset she describes in Elizabeth in Pride and Prejudice.

Of course once the postal system was established it was not only mail which travelled on the coaches, they carried people too, giving poorer people in the parishes a far easier way to travel across Britain. By purchasing tickets for a seat on the mail coach anyone could travel anywhere in stages and the mail coaches would stop at Inns along routes to change horses, meaning passengers could disembark and stop overnight if they wished. The postal service became a big business on which most people were reliant in some way.

Below is an image of the Mail Coach depot in London which I found in a house I visited recently, it’s a bit difficult to view because of the glare on the glass, so there is a closer shot in the slideshow at the bottom of this blog.

You might think that Lady Catherine De Bourgh spoke of the mail coaches in following exert from Pride and Prejudice, ‘I cannot bear the idea of two young women travelling post by themselves. It is highly improper. You must contrive to send somebody. I have the greatest dislike in the world for that sort of thing. Young women should always be properly guarded and attended, according to their situation in life.’ She was not referring to the mail coaches though. If people of gentlemanly birth could not afford their own carriage they hired carriages called a postchaise and I think this is the reference in Pride and Prejudice because following the above scene Jane Austen describes, ‘At length the chaise arrived, the trunks fastened on, the parcels within and it was pronounced to be ready.’

These hired carriages were painted yellow and sometimes called the ‘Yellow bounder.’

Because it came to the door, it cannot have been a mail coach, and in the description of its arrival and loading, I am making the assumption it was not a coach owned by Mr and Mrs Gardiner and sent to fetch Lizzie, but a coach hired from the postal-inn to transport Elizabeth.

When later in the book, Jane describes the visit made by Lady Catherine, she says, ‘their attention was suddenly drawn to the window, by the sound of a carriage; and they perceived a chaise-and-four driving up the lawn. It was too early in the morning for visitors, and besides, the equipage did not answer to that of any of their neighbours… The horses were post; and neither the carriage nor the livery of the servant who preceded it, were familiar to them.’ From this passage we can see another impact of the postal service. Lady Catherine clearly had her own carriage, we know from the previous descriptions of her consequence she could afford it and the servant is in livery so must be her own. Therefore we can assume the carriage is hers. However, Jane describes the horses as ‘post’ I’d love to know how she could tell by looking, they must have borne some mark or branding, but this implies a length to Lady Catherine’s journey, she travelled a long enough distance to call on Elizabeth that the journey had tired her horses and to continue she’d had to hire a change of horses from a postal-inn. So even those who could afford carriages benefited from the postal service in other ways than through it just transporting letters. You can therefore imagine the effect the establishment of the postal service had on Britain, our islands instantly became smaller, and picture the impact on transporting of information between the hubs of business like Bristol and London, two of the ports through which the East India Company operated.

You’ll notice in the two last pictures above, of postchaises painted by Thomas Rowlandson, that there are riders on the horses and people did employ postillion riders to urge the horses on and make a journey faster.

Jane Lark is a writer of authentic, passionate and emotional love stories.

See the side bar for details of Jane’s books, and Jane’s website www.janelark.co.uk to learn more about Jane. Or click ‘like’ on Jane’s Facebook page to see photo’s and learn historical facts from the Georgian, Regency and Victorian eras, which Jane publishes there. You can also follow Jane on twitter at @janelark