The Tradescants ~ The Ashmolean Museum

The first time I came across the sort of collection I am writing about today was in a Phillipa Gregory Novel, one of the earlier ones, a trilogy about John Tradescant and his son, also a John, beginning with Earthly Joys. The two men were gardeners employed by the Earl of Salisbury. They travelled the world to discover plants that would be new to English people. Discovering the unknown and unseen was something to be admired in British Isles then. A way to make a name for yourself, so you would be remembered. The Earl of Salisbury was not particularly remembered for his plant collection. But John and his son John, collected all sorts of things on their trips too and returned home with their botanical gifts for the Earl, but also with geological, zoological and man-made items. They gathered so many curious items they opened a museum called ‘The Ark’ in their home in Lambeth in London in 1634, and charged the public to view their collection. Their collection contained wonderful and curious objects like a stuffed Dodo, a cloak claimed to be that of the American Indian Pocahontas’s father (which it was not, it was a wall hanging), and the hawking glove, hawk’s hood and stirrups belonging to King Henry VIII.

It is the Tradescants’ collection of artefacts gathered from across the globe in the very early days of colonialism, that became the foundation for the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. The younger John Tradescant deeded ‘The Ark’ collection to Elias Ashmole after he’d catalogued the items. As a collector of books and manuscripts Elias was keen to preserve the Tradescants’ collection. But John the younger regretted his decision and in his will left the collection for his wife to earn an income from until her death, with a desire that it be gifted to either Cambridge or Oxford University. John’s wife began selling items, so Elias took her to court. After years of legal argument a court eventually found in his favour, and just before her death in 1678, Edith Tradescant handed over the responsibility for the collection. It was Elias Ashmole who then gave the collection to Oxford University.

The foundation stone of the Ashmoleum museum was laid in 1679. I remember thinking when I read Phillipa Gregory’s trilogy years ago that really the museum should have been The Tradescant Museum.

At the time items the university owned were added to the collection and obviously the museum’s collection has grown over the years. But I always remember it began from one collector, John Tradescant the elder, and what I love is that it’s not a collection of one type of item. As I’ve said Elias Ashmole collected books. John Tradescant collected anything he found interesting, unusual or beautiful, and this is the sort of collection I love.

Sir Thomas William Holburne ~ The Holburne Museum

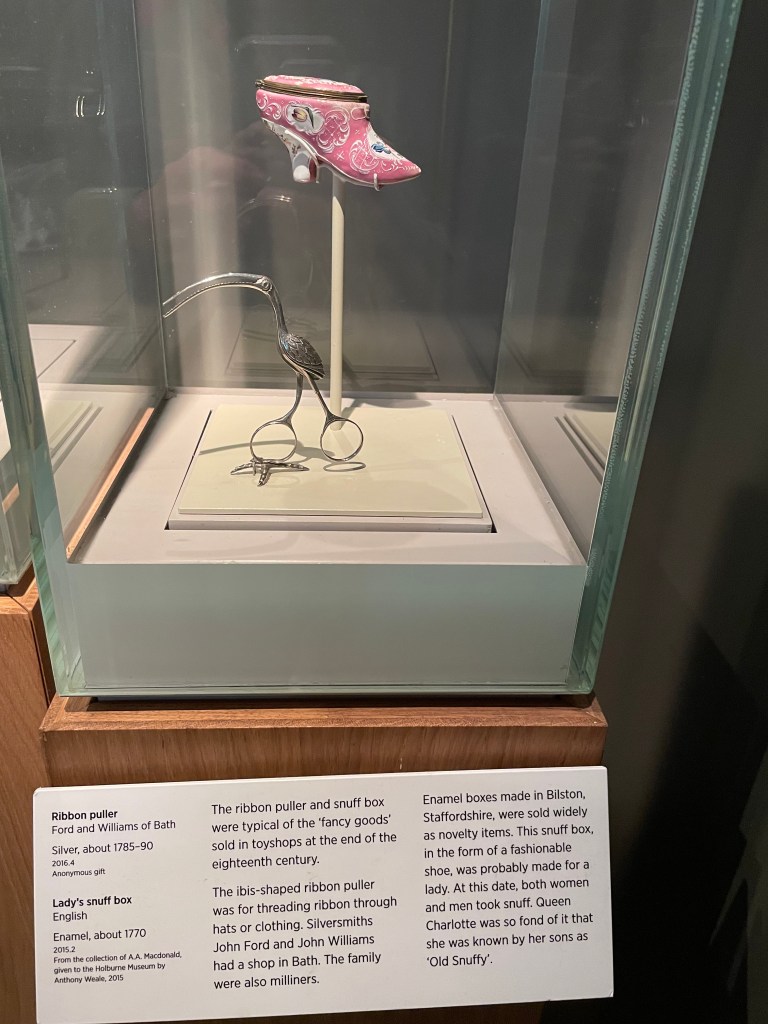

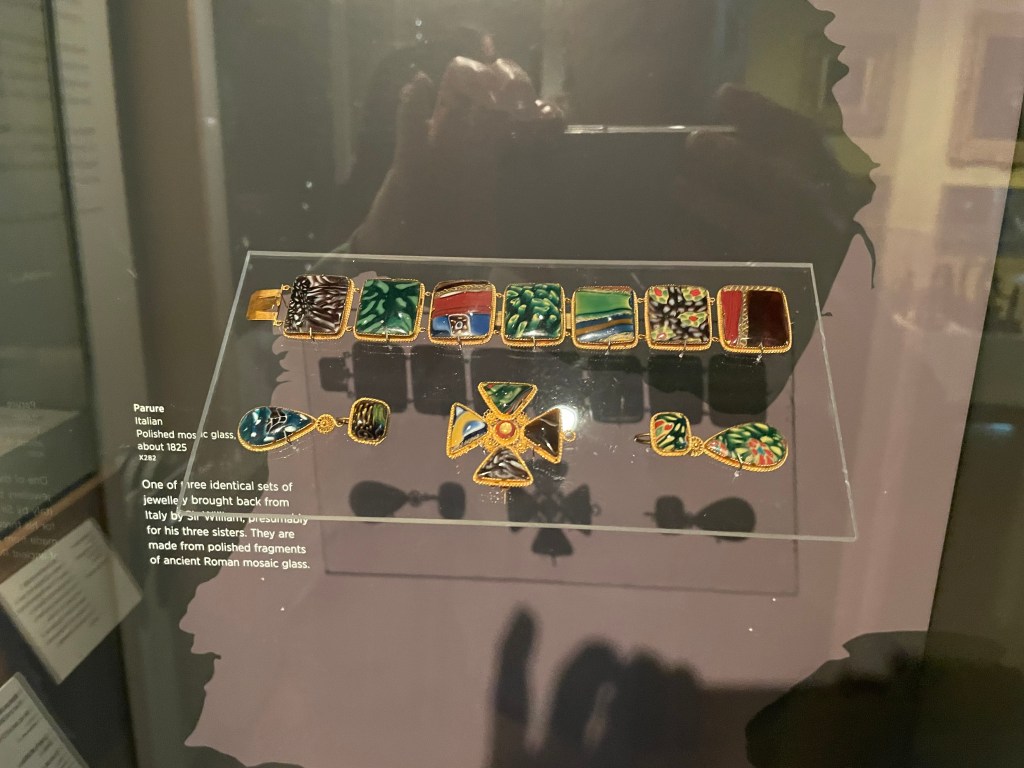

Another museum based on one of these anything I find curious or admire collections is the Holburne Museum in Bath, pictured above (Also known now as, Lady Danbury’s house from the TV Series Bridgerton). Sir Thomas William Holburne lived in Cavendish Crescent in 1830 at the age of 37, with three unmarried sisters. He’d inherited some items of his collection but expanded it considerably, much of it is the sort of item men collected on a coming of age Grand Tour. After his death in 1874, the collection became the property of one of his sisters who when she died in 1882 left the collection to the city of Bath. By this time it consisted of over 4000 items. Her wish was that it became ‘A nucleus of a Museum of Art for the city of Bath.’ Again, many items have been added to the original collection since the museum was opened in 1892. In fact there are pictures of various items from this collection in some of my much older blog posts.

I should say, before I say more, that I am not a hoarder by nature. My parents hang on to too much, and they have to have every gadget there is. So, I have gone the opposite way and if it isn’t used it’s out. But I do have things that they’re only use is I admire them because I look at them and they bring back a memory, of they feel nice to touch, or they’re so interesting I can look at them a hundred times and still be fascinated. This has made me start to appreciate these early collectors more.

William Murray & Elizabeth Murray ~ Ham House

So why have I chosen today to talk about curious collections? Because Ham House, that I wrote about last week, had my favourite collection. William Murray, 1st Earl of Dysart, who King Charles I gifted Ham House too, was also a collector in the 1600s, in the same era as John Tredescant. As I said last week the house is a time capsule, and his collection room is too. The Green Closet was created in 1637, five years before the English Civil War and twelve years before his friend Charles I was beheaded.

As you can see above, the collection is mostly portraits and paintings. William died before Charles II was restored to the throne. But it was noted In 1677, after his death and post the English Civil War, the collection consisted of 57 paintings, including many precious original miniatures. One being of Queen Elizabeth I. There are also two lacquered cabinets from Japan dating to around 1630. I would guess the collection was hidden away during the Civil War and reinstated in the room after this by his daughter, when at the same time his daughter, Elizabeth , had a silver mounted ebony table made, which is decorated with her monogram, incorporating her title Countess of Dysart.

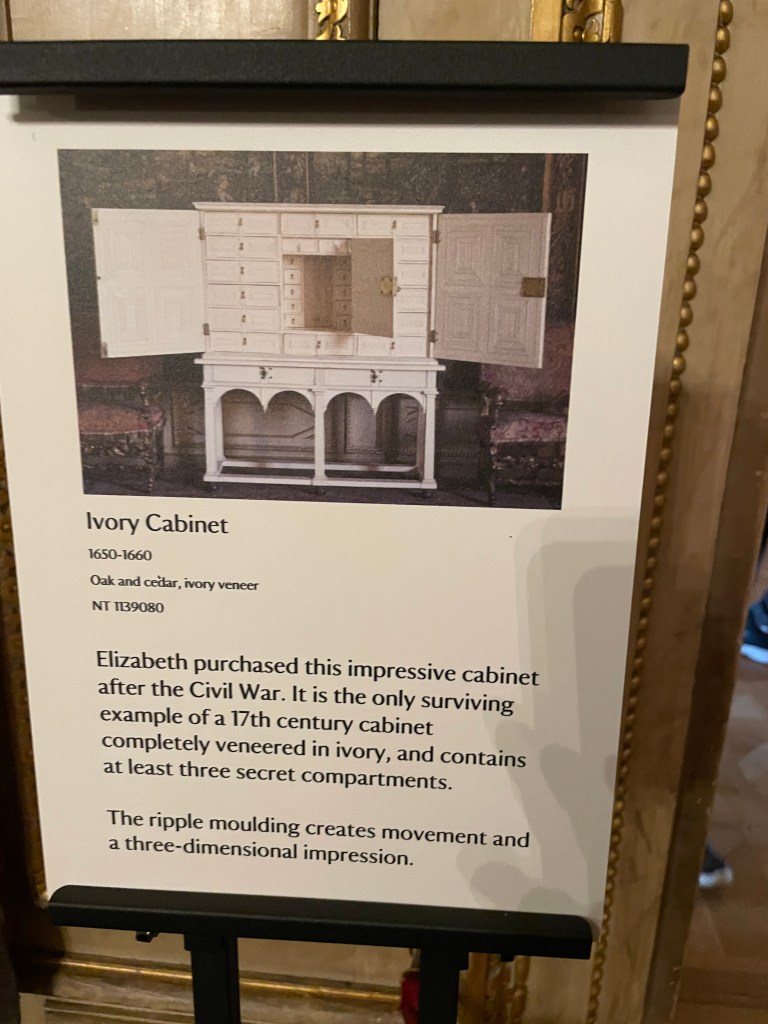

The Murray collection is not eclectic, which is what I love about the others, but it’s the way he created a room for his precious things in the 1600s, to keep the things he valued most (Perhaps the Tradescants ‘The Ark’ room was similar, though, they had nowhere near as much money to make the space pretty and would have needed a larger room). It’s also wonderful that the family have retained that room. But then his daughter, Elizabeth, who reinstated the room and mounted the Japenese cabinets, became a collector too. Of cabinets.

All the cabinets she collected are opened once a year for the public to see just how clever the craftsmanship is and why she must have thought them beautiful and precious.

Beatrix Potter ~ Hill Top

There is just one more collection I would like to share, and that is a very different one. Again I have mentioned in a blog before that Beatrix Potter’s house, Hill Top, in the Lake District, was a holiday home that became her office, never a place where she lived, so in one way the whole house is a collection of things that inspired her writing. However there is one cabinet that draws my eye every time we visit her house, and it is a collection of complete oddities, I would not even say rarities or valuables. Well not valuable in the money sense anyway. The things in the cabinet must have held some emotional value to her. The items, though, are completely random. The most eclectic collection I have ever seen!

And in the future me

So now, guess what? I want to start my own, definitely eclectic, collection. I shall have just one cabinet, and I think it will contain whatever interests me. Modern or old. Artistic or silly. Beautiful or ugly. Tactile or uncomfortable. The only common thing will be that the cabinet will express my personality.

Feel free to tell me about your curious collections in comments 😀